January 2011

prepared by: David Kent Ballast Architectural Research Consulting

Introduction

Purpose of the project

Accessibility standards reference industry guidance in the measure of field and construction tolerances. However, few trade and materials specifications include tolerances for features that are relevant to usability by people who have disabilities. For instance, when this project began, tolerances for the measurement of the slope, flatness, and smoothness of exterior walking and rolling surfaces in concrete, asphalt, unit masonry, and other materials had not yet been developed by industry groups.

The current project was undertaken to encourage and support construction industry stakeholders to fill in the gaps in existing tolerances and procedures and to set specific tolerances and procedures for measurement for particular materials and assemblies. The purpose was not to suggest or revise the dimensional limits set in the ADA/ABA Accessibility Guidelines nor to set specific tolerances within the body of the Guidelines, but rather to assist industry in developing dimensioning and measurement conventions appropriate to the different materials and methods used in exterior and interior walking/rolling surfaces so that practitioners and regulatory agencies could refer to them for guidance.

The Access Board contracted with David Ballast, FAIA, CSI with Architectural Research Consulting to manage the project and provide assistance and advice to industry associations as required to meet the goals of the project.

Background

While the current ADA/ABA Accessibility Guidelines (ADA/ABA Guidelines) make reference to standard industry construction tolerances as they relate to the dimensions given in ADA/ABA Guidelines, architects, contractors, code officials, courts, and others still have questions about what is required with respect to accuracy in dimensioning and constructing accessible elements. The position of the U. S. Access Board - as formalized in the ADA/ABA Guidelines in Section 104.1.1 - is that industry standard tolerances should be relied on when questions regarding this issue arise. However, few trades have codified specific tolerances for many of the elements mentioned in ADA/ABA Guidelines, nor have they developed accepted industry protocols for measuring when questions of accessibility arise. This is especially the case with issues related to surfaces. Further, industry standards, specifications, and measurement procedures do not even address some measures important to facility usability in new construction, such as how to measure the slope and flatness of a ramped surface designed for accessibility.

The absence of specific direction from industry regarding these issues creates significant problems for users trying to comply with surface accessibility requirements. These problems include increased construction costs, unnecessary demolition and rebuilding, litigation, uncertainty, and - too often - animosity among members of the building team, regulatory agencies, and the disabled community.

U.S. Access Board staff report that a large number of calls to their technical assistance hotline from architects, contractors, and others are seeking clarification of tolerances for specific materials or assemblies. Anecdotal evidence of the need for greater specificity also exists as comments from architects, contractors, building owners and managers, the disabled community and regulatory agencies. In the absence of clear direction, tolerances have often been determined by the courts. Evidence of these problems was significant enough that the U.S. Access Board funded this project to deal with them.

Many trade groups have developed standard tolerances for certain aspects of construction. In particular, valuable work has been done on the measurement of flatness, smoothness, and vibration for some applications. The accompanying list of publications in Part 3 of this report includes references to many of these resources. In addition, a number of organizations and individuals have attempted to develop general guidance for tolerances based upon ADA/ABA Guidelines provisions. These plus - or - minus allowances have generally not been based upon materials and fabrication criteria that underlie standard industry tolerances, nor have any testing protocols been provided for their measure.

Construction tolerances, measurement protocols, and related issues affect all areas of construction where there is a concern for accessibility. Some of the questions and problems related to construction tolerances may also raise issues of metrology - selecting appropriate units of measure and significant digits and establishing appropriate measurement protocols. Local practice adds another dimension to the issue.

This project focused on surface measures, including slope, flatness/waviness, smoothness, and planarity with respect to the various materials used for exterior walking and rolling surfaces.

In order to eliminate uncertainty in compliance with accessibility standards, the Access Board believes it is best for industry stakeholders to fill in the gaps in existing tolerances and procedures and to set specific tolerances and procedures for measurement. As part of this project tolerances have been established by the Tile Council of North American, the Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute, and work is underway by the Brick Industry Association. Part 1 of this report summarizes these efforts. Unfortunately, other industries and trade groups were reluctant to establish additional tolerances for their materials and assemblies. Part 2 of this report includes early work by the concrete industry to develop tolerances and measurement protocols.

-

Part 1 of this report summarizes the tolerances developed by those industries that participated in this project. It also includes other work that is ongoing by other groups and agencies.

-

Part 2 of this report provides suggested best practices for designers and the construction industry as a way to avoid construction tolerance problems. It also includes suggested tolerances and measurement protocols that the concrete industry may want to consider in developing an industry standard. These tolerances and measurement protocols could also be used by other industries that use their materials for both exterior as well as interior accessible surfaces.

-

Part 3 of this report includes some of the background information that was generated during the course of this project.

Part I

Summary of the project

Throughout the course of the project representatives from various trade organizations that represent the following materials that may be used for exterior surfaces were invited and encouraged to participate to develop industry standard tolerances, installation methods, and measurement protocols unique to the individual materials their organizations represent.

- Asphalt

- Brick

- Concrete (poured)

- Concrete pavers

- Metal (solid and grating)

- Stone

- Tile

- Wood (dimensional lumber and panel surfaces)

In addition, the following professional organizations and private companies were invited to participate to develop best practices for design and construction.

- American Institute of Architects

- Construction Specifications Institute

- Master specification writing companies

Other interested parties were also involved in the project including contractors, building owners and managers, a landscape architect, a rehabilitation researcher, and representatives from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the National Institute of Building Sciences.

There was a two - phase process to discuss issues, share knowledge and information, and set direction for future work for individual industries and trade groups. Phase 1 was completed in spring, 2007 in a workshop that brought together 14 representatives of users of tolerances data - - design professionals, contractors, code officials, facility providers, and others. During this workshop (www.access - board.gov/news/tolerances - workshop.htm) the following conclusions were established:

a) measurement protocols for exterior walkways must be appropriate to need, material, and construction methodology;

b) rollability measures for walkway smoothness, flatness, and planarity may be adapted from roadway standards, although this may be problematic;

c) the use of the F - number system in exterior surface measurement may not be appropriate;

d) the effect of different tolerances for different walkway materials is a concern;

e) accumulated tolerances must be addressed;

f) repair, alterations, and maintenance of exterior surfaces are also issues;

g) training, availability, and skill levels of construction workers must be considered;

h) contractors and others responsible for compliance want a more clearly defined set of requirements.

Phase 2 of the project focused on the following:

- to work with trade associations to encourage and support them in the development of materials - specific tolerances;

- to encourage organizations such as the AIA, CSI, and master specification providers to develop and communicate “best practices” for the design, construction documentation, and specification of tolerance and measurement information for walking and rolling surfaces covered by accessibility standards;

- to continue to coordinate with ACI on their efforts, already underway, to address tolerance standards and tolerance compatibility;

- to pursue the development of measurement protocols for ramps and walkways in a range of surface materials; and

- using information gained from this phase, to expand our efforts to include the development of industry tolerances beyond surfaces, where they currently do not exist.

Of the industries that were asked to participate only the Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute (ICPA) and the Tile Council of North America (TCNA) developed and published guidelines for tolerances related to accessible surfaces. The Brick Industry Association is currently working to develop their standards. The American Concrete Institute (ACI) began development of guidelines as part of another document the 117 Committee (Tolerances) was working on but these guidelines were subsequently deleted from the document during its development. These efforts are summarized below and copies of the documents included in Part 3 of this report.

Throughout the course of the project it was very difficult to engage many of the trade groups. It appeared there could be several reasons for this.

First, trade and professional groups may be reluctant to develop standards related to accessibility that could have legal consequences.

Second, trade groups have certain priorities, such as the promotion of a specific material and technical assistance to contractors, architects, and other industry members. With limited staff and funding, they may not be willing or able to take on additional standards development. They may also feel accessibility standards are not within their realm of responsibility or interest.

Third, the typical structure of a trade group makes it difficult to complete standards development. Trade organizations vary in their size, membership, funding, and type of full - time administration support. Most trade associations rely on volunteer participation of their membership to develop standards and produce publications, which takes a significant amount of (generally unpaid) time. Leadership also varies, ranging from members elected to short - term positions (a president, for example) to full - time (and long term) administrators with extensive office support. A long - term project often lacks a continuity of leadership and commitment, especially in smaller organizations. A limited budget may also prelude participation.

Current industry standard practices resulting from this project

Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute (ICPI)

The ICPI, along with the Brick Industry Association and the National Concrete Masonry Association, funded research in 2002 to evaluate the vibration exposure during electric and manual wheelchair propulsion over several types of sidewalk surfaces. Studies were repeated in 2003 and 2004 to determine the effects of environmental factors and evaluate additional surface types. The research was conducted by the University of Pittsburgh Human Engineering Research Laboratory and was based on exposure limits of vibration to the human body established in ISO 2631, Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole - Body Vibration.

Based on this research, it was determined that some types of pavers (both square edged and beveled) and installation methods were an acceptable type of exterior paving. With the encouragement of the Access Board project, ICPI developed recommendations for segmental concrete pavement and installation tolerances based on the research they funded.

Refer to the ICPI document in Part 3 for the detailed recommendations and construction tolerances that were developed.

Brick Industry Association (BIA)

The BIA participated in the funding of the research conducted at the University of Pittsburgh and two brick paving patterns were tested along with the concrete pavers. The BIA agreed to develop surface tolerances as part of the Access Board project. These are currently under development.

Tile Council of North America (TCNA)

The TCNA participated in this project and developed guidelines for ramp slopes, changes in level, flatness and lippage. These were published in the 2009 edition of the TCA Handbook for Ceramic Tile Installation. Refer to the TCNA document in Part 3 for the full text of the guidelines.

Areas for further work

In the process of assisting the various organizations that represent surface materials and professional groups the following issues were identified as parameters that might be considered in the development of any industry standards. Of course, it was not expected that all of these would be included in any one industry’s standards, but they do indicate the range and complexity of issues related to construction tolerances and accessibility, both with surfaces and any other aspect of accessible construction. This list may be useful for any future work.

Design issues:

- Existing industry tolerances

- Units of measure

- Measurement instruments

- Accuracy of instruments/measurement uncertainty

- Use of significant figures

- Metric conversions or dual unit standards

- Measurement of dimensions that involve two or more trades/materials

Construction issues:

- How/where to take measurements/precision of measurement

- Accuracy of construction/tolerances for individual materials

- Cost/time implications

- Influence of accepted local practices for construction

- Inspection/measurement protocols

- Effects of weather, such as curing and freeze - and - thaw on outdoor surfaces

- Maintenance/durability of surfaces

- Workforce training

Usability issues:

- Planarity

- Maneuverability

- Rollability/rolling resistance

- Jointed surfaces/vibration

- Cross slope

- Gaps

- Flatness lippage

- Slip resistance

In the end, most of these issues were not considered by the trade and material organizations that participated in this study or reference was simply made back to the ADA/ABA Guidelines. This may be due the time and effort required to consider them all or to the reluctance of an organization to commit to the development of standards that could have legal consequences.

Part II

Suggested best practices for architects and other design professionals

As the construction industry works to develop standards for construction tolerances related to specific materials and applications for accessible surfaces, design professionals must also work to minimize problems caused by tolerance issues. In fact, one of the easiest ways to avoid problems is to design construction elements that take the reality of construction tolerances into account.

Design professionals have the tools with existing construction practices to minimize problems with construction tolerances. It is simply a matter of clearly communicating four things: (1) what is wanted, (2) the standards used, (3) how compliance will be verified, and (4) what the result of noncompliance will be. Of course, if industry standards do not exist, the architect or designer must create their own for each project. The following suggestions describe how design, drawings, specifications, pre - construction meetings, and construction observation can be used in this effort. In some cases, designers can use these tools as they exist. In other cases only slight changes may be required to adapt them to communicate and achieve accessibility requirements.

1 - Design and drawing

Current practice

It is typical practice for architects to use the values published in guidelines and standards and repeat the values on the drawings. If the value is a minimum or maximum or a range, this fact may not be communicated to the contractor, who may think that there is a tolerance allowed.

In the preamble adopting the 2004 guidelines as the 2010 Standards for Accessible Design the Department of Justice clarified Sections 104.1 and 104.1.1 saying that conventional industry tolerances apply to absolute dimensions (for example, a single number) as well as to dimensions that are stated as either a minimum or maximum value. Tolerances do not apply where a requirement states a range; for example, that grab bars must be installed between 33 inches and 36 inches above the finished floor.

In addition, current practice for architectural and construction engineering drawings establish ambiguity and the potential for accumulated measurement error. For example, architects typically use chain dimensioning. If the contractor follows the chain in layout, slight errors can accumulate to the final dimension.

It is also not standard practice to assume that a fractional measurement indicates a significant figure or the implied accuracy required. An architect may dimension something as 14’ - 6 ½” and want that to be built within a 1/16 - inch tolerance, not a ±1/4 - inch tolerance as the value 6 ½ inches indicates because of rounding. It is not standard practice to label the dimension as 14’ - 6 4/8” to communicate this.

When a dimension is especially important, drafters may use the word “HOLD” or some similar word to indicate that a dimension is important. Less important dimensions may have a ± as a suffix to indicate that this dimension may vary slightly, although this practice is seldom used. In both cases the amount of the allowable variation is not clear.

Although significant figures could be used as a way to state expected accuracy or certainty in a measurement, the practice of using feet, inches, and fractions of an inch do not allow this as the method is currently used. However, the use of SI units can imply the accuracy intended by varying the number of digits beyond the decimal place.

1.1 Best practices for design

1.1.1 When a maximum or minimum dimension is a regulatory requirement use a drawing dimension that is less than a maximum limit or more than a minimum limit. The dimension should be determined by the expected tolerance of the construction element.

The simplest way for design professionals to avoid problems with construction tolerances related to surface accessibility and other accessible elements is to design for slopes and dimensions that are slightly less than maximums and slightly more than minimums. For example, the 1:12 slope stated in ADAAG and ADA/ABAAG is a maximum slope for ramps, not a design requirement. ADAAG and accessibility experts recommend that ramps be built with the least slope possible but in no case should a ramp exceed a 1:12 slope (except for curb ramp flares, and other approved exceptions). Although ramps with a slope slightly less than 1:12 take up more floor space, the negligible loss in usable space will more than compensate for potential problems caused by rebuilding or litigation due to ramps exceeding the 1:12 slope.

1.1.2 When a dimension range is the regulatory requirement use the midpoint of the range as the drawing dimension.

1.1.3 A maximum overall design running slope for exterior accessible surfaces (other than ramps), such as sidewalks, of 4% (approximately 1:25) is recommended. In the ideal case, planning for a 4% running slope allows for construction inaccuracies while still not exceeding the maximum 1:20 slope for walking surfaces.

1.1.4 A maximum overall design running slope for exterior accessible ramps of 7.5% (1:13.3 or 1:13) is recommended. This allows for a potential plus tolerance of approximately 0.8% while not lengthening the ramp excessively. This also minimizes the effects of local variation while not lengthening the ramp excessively. Complying with a tolerance of +0.8% is generally possible with common methods of constructing ramps with concrete, asphalt, and pavers.

1.1.5 A maximum design cross slope for accessible exterior pedestrian paving and ramps of 1.5% (1:67 or about 3/16 in. per ft. [15 mm per m]) is recommended. This allows for a potential plus tolerance of +0.5% while still providing for drainage. ADA/ABAAG states a maximum cross slope requirement of 1:48 (1/4 in./ft. [20 mm/m] or about 2%). Pervious concrete may also be considered for surfaces that are designed to be nearly level.

1.1.6 Accessible surfaces should be as smooth as possible. This includes localized variations in slope as well as bumpiness created by small, individual units such as bricks, concrete pavers, or wood slats.

In most cases using concrete or asphalt minimizes the potential problems with bumpiness. However, smaller paving units may be used if the gap between the units and the lippage (difference in offset between units) is minimized. As a guide, research conducted at the University of Pittsburgh on concrete pavers found that limits on whole body vibration as established in ISO 2631, Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole - Body Vibration were not exceeded if the bevel on the units was less than or equal to 6 mm (1/4 in.) and the pavers were placed in a 90 - degree herringbone pattern.

Local variation in slope can also be a problem for users of wheelchairs and other mobility aids. For example, although a ramp may meet the overall slope requirements of 1:12, a dip or hump along the ramp may create a stumbling hazard or a short incline greater than 1:12. Specifications should include limits on how many local variations will be accepted and the methods by which accessible surfaces will be measured.

For accessible surfaces constructed of small, individual units, such as concrete pavers or wood slats, the drawings (along with the specifications) should include the best method to install the material to minimize variations in smoothness and maintain a uniform surface over the life span of the material.

1.2 Best practices for drawing

1.2.1 Use the plus - or - minus symbol (±) after a dimension when it must be made clear what the expected tolerance is. This should be coordinated with the specification requirements. Although current practice dictates that tolerances only be included in the specifications, many workers reading the drawings do not read the specifications so it makes sense to show critical tolerances on the drawings as well. Also include a general note stating that no additional allowances either plus or minus will be allowed. For example, use a format such as 6’ - 4” (±1/8”) or 1930 (±3 mm).

1.2.2 Use datum dimensioning referenced to a primary or secondary control point on the construction site when the position of one item is particularly important. Do not dimension it based on one or more dimensions in a string.

2 - Specifications

Specifications provide an ideal place to prevent many of the problems associated with construction tolerances. Specifications allow the requirements to be stated as succinctly or as elaborately as required. The four items that should be communicated as stated in the introduction to this guide can clearly be defined in the specifications with corresponding dimensions shown on the drawings. These include: (1) tolerance requirements (what is wanted), (2) the standards used, (3) how compliance will be verified, and (4) what the result of noncompliance will be.

If specific tolerances or requirements are not stated in the specifications (or drawings) it is generally held by the courts that industry standards apply. However, many industries do not have tolerance standards or the problematic element may be part of a larger assembly for which there are no standard tolerances, the placement of a toilet, for example. When tolerances do not exist and there are no clear standards, disputes arise and the courts may decide the issue, with the accompanying cost and time implications for the design professional. If there are conflicts between drawings and specifications, specification requirements generally override the drawings.

Current practice

Nearly all architects use the 3 - part format, developed by the Construction Specifications Institute, for writing individual specification sections. The 3 - part format has places to include all requirements related to tolerances and measurement protocols. One or more of them should be used as needed to describe the requirements of a project. These include the following.

- References to industry standards: Part 1, References

- Required test reports (third - party verification) and similar documents: Part 1, Submittals

- Mockup requirements: Part 1, Quality assurance

- Regulatory requirements and pre - installation meetings: Part 1, Quality assurance

- Shop fabrication of elements: Part 2, Fabrication tolerances

- Special techniques and interface with other work: Part 3, Construction requirements

- Final, installed tolerances: Part 3, Site tolerances

Many manufacturers and trade groups have guide specifications that include their product’s tolerances. In addition, master specifications, such as SPECTEXT® and MasterSpec® include tolerances in many of their sections.

2.1 Best practices for stating tolerances in the specifications

2.1.1 Clearly state the required installed tolerances for critical construction elements. In most cases, it is best to refer to industry standard tolerances or other industry documents when they exist. For example, ACI 117, Specifications for Tolerances for Concrete Construction and Materials and Commentary can be included without having to list the hundreds of individual tolerances given in the standard. If tolerances stricter than those given in an industry standard are required for a specific project, these should be stated, with the recognition that tighter tolerances may increase construction cost or time or both.

2.1.2 State the required tolerances for elements for which there are no industry standards. These may also include elements for which there is an industry tolerance for one aspect of the element but not others. For example, a product may have a manufacturing tolerance and an installed positional tolerance but not have an orientation tolerance for plumb.

2.1.3 State requirements for critical accumulated tolerances. These are instances where individual products and installation procedures may conform to industry standard tolerances but the final installed element may not meet regulatory, functional, or aesthetic requirements.

\

2.2 Best practices for stating standards

2.2.1 List all applicable industry standards that define tolerances and measurement protocols, if any.

2.2.2 Set requirements for independent testing agencies that may be required to perform measurement for compliance. Specify the measurement tools that should be used to determine compliance with the tolerances.

2.3 Best practices for stating how compliance will be verified

2.3.1 Define the measurement protocols to be used to check for compliance with the tolerances and standards. This may include where measurements are made, how many should be made, and the number or percentage of measurements that must fall within the limits to be considered acceptable. For example, specifications may include limits on the number of local variations (dips and humps) on an accessible ramp to a maximum of 10 percent slope for no more than 20 percent of the measurements taken. If industry standards exist for measurement protocols, these should be referenced.

2.3.2 Define the measurement tools that should be used. The acceptable tools should be selected based on the accuracy required and a reasonable balance between the accuracy of the tool and the time, cost, and experience required for measurement. For example, floor profilers can provide a very accurate measurement of surface flatness but are expensive and require training to use. For exterior surfaces, a surveyor’s transit or digital inclinometer may provide acceptable measurement for the same task.

2.4 Best practices for stating the result of noncompliance

2.4.1 Based on the methods for measuring compliance, define what remedial actions are acceptable when construction elements exceed tolerances. These may include total replacement, partial replacement, adjustment, moving, filling, patching, or other operations as appropriate for the construction element.

2.4.2 When defining acceptable methods of correction for a non - complying element, give reasonable consideration to how the remedial action may affect construction time, cost, adjacent construction, and appearance. If possible, give the contractor options for how the element may be brought into compliance.

3 - Best practices for pre - construction meetings

Pre - construction meetings provide another commonly used technique to communicate the required needs of the project. All interested parties are together (or on a conference call or teleconference). The designer can ask if everyone has read the specification requirements and interpreted the drawings correctly. Unusual or particularly tight tolerances can be discussed, questions asked, construction techniques suggested, measurement methods outlined, and how compliance will be checked can all be brought into the open. Requirements for pre - construction meetings should be clearly stated in the specifications.

4 - Best practices for construction observation

Construction observation is the final step in building an accessible element to meet design and regulatory requirements. Even though the final responsibility rests with the contractor, the architect, or other design professional should be observing construction and requiring the contractor to use the measurement protocols outlined in the specifications. For large projects for where extensive accessible surfaces are required, early checking should be done to suggest needed adjustments to construction techniques. The final check, of course, is with the regulatory agencies.

Suggested accessibility guidelines for exterior concrete surfaces

Current standards for ramps, sidewalks, and intersections and other concrete tolerances are given in ACI 117, Specification for Tolerances for Concrete Construction and materials and Commentary. The following tolerances may be applicable for exterior accessible surfaces. Other tolerances and measurement protocols are given using various methods but these are for interior surfaces.

- For exterior ramps, sidewalks, and intersections, in any direction, the gap below a 10 - foot unleveled straightedge resting on highspots shall not exceed +1/4 inch (6 mm).

- The tolerance for the top surface of a slab - on - ground is ± 3/4 inch (19 mm).

- The deviation from slope or plane of formed surfaces over 10 feet (3 m) is ± 0.3% of length. This is approximately 3/8 inch in 10 feet (10 mm in 3 m). However, the ACI standards do not permit interpolation or extrapolation for dimension greater than or less than 10 feet.

- The tolerance for deviation from slope or plane for a stair tread from the back to the nosing is ± ¼ in (6 mm).

- The difference in the height of adjacent risers of stairs measured at the nosing shall not exceed 3/16 inch (5 mm).

If a more detailed method of specifying tolerances and measurement protocols are required the following are suggested. These suggestions are detailed enough to provide information necessary to determine if the surface is suitable for the majority of disabled users but simple enough to allow workers of various skill levels using basic tools to complete the necessary measurements for installations of all sizes.

1 Accessibility for walks, ramps, and stairs

1.1 Measurement protocols

1.1.1 Measurement tools. Distance measuring devices should be capable of measuring to a precision of 1/16 in. (1 mm). Angular or slope measuring devices should be capable of measuring to a precision of 0.1 degree and elevation measuring devices should be capable of measuring to a precision of 0.01 ft (1/8 in. or 3 mm).

For measuring device accuracy, the instrument and technique for measurement should provide for an accuracy of at least one - third the required tolerance. For tolerance measurement requirements of 1/8 in (3 mm) this would mean a device capable of measuring to about 3/64 in. Because this is not realistic in construction, a tape measure with 1/16 in. divisions is a reasonable compromise for inch - pound units. For metric measure, most tapes are marked in 1 mm units, which make them ideal for determining 3 mm tolerances.

If some tolerances are set at 0.5% slope (0.2865 degrees or approximately 0.3 degrees), then the accuracy of the instrument for measuring slope should be ±0.1 degree. Digital inclinometers (SmartTool®), floor profilers, and other electronic instruments are capable of measuring to this accuracy. 0.01 ft accuracy for elevations is common in surveying and nearly all instruments, including metal tapes, can achieve this accuracy.

1.1.2 Walks. Measure walks and other non - ramp pedestrian surfaces for overall running slope and cross slope as well as local running slope and cross slope variations (flatness) in accordance with 1.1.3, 1.1.4, 1.1.5, 1.1.6, and 1.1.7. This includes surfaces with a maximum slope of 1:20 (5%), such as a walk, parking area, or a portion of a driveway that is also used for a walking surface.

1.1.3 Walk running slope. Measure for overall running slope (the primary direction of travel) by determining elevations at the ends of the walk, noticeable changes in slope, or at a maximum of 20 ft (6 m) intervals beginning at one end of the walking surface. Elevations should be measured at the midpoint of the width of the walking surface. Calculate the slope using the horizontal distance between elevation points and the difference between the elevations at those points (i.e. the rise over the run).

1.1.4 Walk cross slope. Measure for overall cross slope (the direction perpendicular to the running slope) by establishing elevations at the outside edges of the walking surface at 10 ft (3 m) intervals beginning at one end of the walking surface. Calculate the cross slope at these locations using the horizontal walking surface width and difference between the measurement elevations at the edges of the walking surface (i.e. the rise over the run).

If an obvious change in cross slope occurs between measuring points (such as a steeper driveway crossing a sidewalk), measure a minimum of two cross slopes at the steeper portion, but in no case should the measurements be farther apart than 5 ft (1.5 m).

A simple method of establishing the relative elevations is to use a rotating laser level on a tripod and document the difference in height on a stiff metal tape measure or surveyor’s rod. Alternately, a surveyor’s transit or other electronic surveying tool may be used if it meets the accuracy requirements of 1.1.1. For walkways that are narrower than the length of a carpenter’s level, the instrument may be placed level, resting on the high edge of the walk, and the distance from the level to the low edge of the walk may be measured to determine the difference in elevation.

The methods in 1.1.3 and 1.1.4 of establishing the running slope and cross slope is consistent with the requirements of ADA/ABA - AG, which limits the running slope and cross slope of walking surfaces to 1:20 and 1:48, respectively. Slopes greater than 1:20 are considered ramps and must conform to the requirements for ramps. Currently, these are the only ADA/ABA - AG standards related to running and cross slope that must be met.

In the draft guidelines for public rights - of - way (which are not yet final) an exception for slope is granted to sidewalks that follow the natural slope of the adjoining street or grade even though it may be steeper than 1:20.

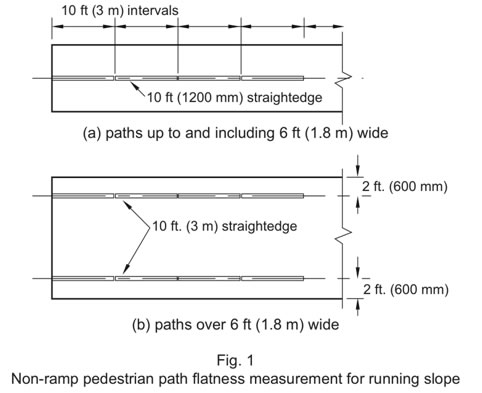

1.1.5 Flatness of walk running slope. For pedestrian paths up to and including 6 ft (1.8 m) wide, measure for flatness of the running slope at 10 ft (3 m) increments along the midpoint of the width of the walk by using a 10 ft (3 m) unleveled straightedge resting on high spots. Measure the distance between the straightedge and the surface at the largest gap. See Fig. 1(a). Alternately, electronic devices may be used that provide an equivalent 10 ft (3 m) flatness measurement.

For pedestrian paths over 6 ft (1.8 m) wide, measure for flatness of the running slope at 10 ft (3 m) increments along two paths, each 2 ft (600 mm) from the edge of the path. Using a 10 ft (3 m) straightedge resting on high points, measure at 10 ft (3 m) increments along the two lines. Measure the distance between the straightedge and the surface at the largest gap. See Fig. 1(b).

This method of measurement is consistent with the tolerance requirements of ACI 117 and can check for localized flatness. However, this section defines where the measurements should be taken.

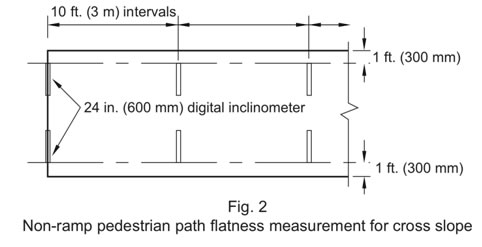

1.1.6 Flatness of walk cross slope. For walks and other pedestrian paths, measure flatness of the cross slope by placing a 24 - in. (600 mm) digital inclinometer perpendicular to the line of travel at 10 ft (3 m) intervals with not less than two measurements. Measure along two paths, each with the end of the digital inclinometer 1 ft (300 mm) from the edge of the path and placed toward the middle of the path. See Fig. 2. If the path is less than 6 ft (1.8 m) wide the ends of the measurement will overlap at each interval.

This method of measurement is based on the assumption that most accessible exterior walks will be at least 60 in. (1525 mm) wide due to passing requirements and that users will tend to stay toward one side or the other when traveling, approximately 1 ft (300 mm) from the edge. This method will reveal problematic variations in cross slope even though the overall cross slope may meet the 1:48 (2%) limitation.

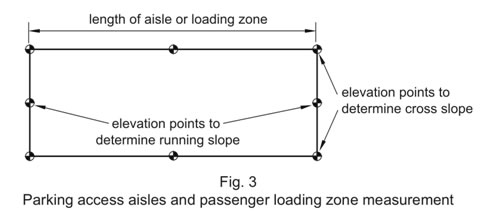

1.1.7 Measurement of parking areas. Only accessible access aisles and passenger loading zones that are part of a larger parking area need to be measured. These areas should be considered as a pedestrian walk with a minimum width of 60 in. and a length of approximately 20 ft and with an ADA/ABA - AG maximum slope of 1:48 in both directions. Overall running slope (in the long dimension) and cross slope (in the short direction) should be measured according to Section 1.1.3 and 1.1.4. This means that the overall slope in the long dimension should be measured along the center of the aisle or zone using the ends of the area as elevation measuring points and cross slope should be measured at each end of the area and at the midpoint of the area. See Fig. 3.

1.1.8 Alternate measurement tools. Walks may be measured with instruments other than a digital inclinometer if they provide the data required for evaluation of tolerances as given in Sections 1.2.1, 1.2.2, and 1.2.3. If the F - number system is used pedestrian paths should have a minimum FF of 25. Running slope should be measured along the same lines of measurements as given in Section 1.1.3.Although the F - number system can be used to measure surface flatness for smooth surfaces it requires expensive equipment and workers trained to do the measurement.

An FF of 25 provides for a flatness of approximately ¼ in. in 10 feet (6 mm in 3050 mm). Waviness index may be a more appropriate measure to include if floor profilers are used.

1.1.9 Horizontal gaps and vertical alignment. Measure for local horizontal discontinuities and variations in vertical alignment such as at concrete joints, gaps, grade breaks, and at the interface of concrete with other materials or elements built into the surface. Measuring devices should be capable of measuring to a precision of 1/16 in. (1 mm).

Requiring a measuring precision of 1/16 in. (1 mm) allows measurements to be made to the nearest 1/8 in. (3 mm) without interpolation and allows the use of commonly available measuring tapes.

1.1.10 Ramps. Measure accessible ramps for overall running slope and cross slope as well as local running slope and cross slope variations (flatness) in accordance with Sections 1.1.11, 1.1.12, 1.1.13, and 1.1.14. Accessible ramps include curb ramps as well as other exterior ramps.

1.1.11 Ramp running slope. Measure for overall running slope of ramps by determining elevations at the top and bottom of the ramp at the midpoint of the width of each ramp run and calculate the slope using the horizontal ramp length and difference between top and bottom elevations (i.e. the rise over the run).

1.1.12 Ramp cross slope. Measure for overall cross slope of ramps by establishing elevations at the extreme edges of the ramp at the top and bottom of the ramp and calculate the cross slope at these two locations using the horizontal ramp width and difference between elevations at the edges of the ramp (i.e. the rise over the run). A simple method of establishing the relative elevations of the top and bottom of each ramp is to use a rotating laser level on a tripod and document the difference in height on a stiff metal tape measure or surveyor’s rod.

This method of establishing the running slope and cross slope is consistent with the requirements of ADA/ABA - AG, which gives the standard for running slope and cross slope as 1:12 and 1:48, respectively. Currently, these are the only ADA/ABA - AG requirements related to running and cross slope that must be met.

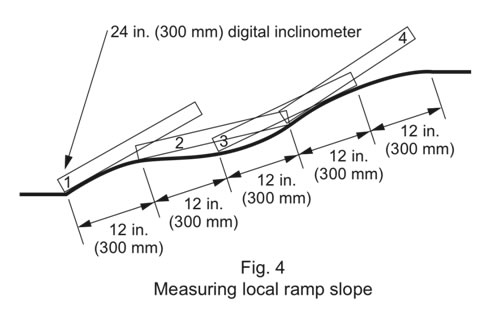

1.1.13 Flatness of ramp running slope. Measure flatness in the running slope of ramps at 12 - in. (300 mm) increments by using successive, overlapping 24 - in. (600 mm) lengths using a 24 - in. digital inclinometer. For each measurement lay the instrument such that it reads the steepest slope or spans between two high points. See Fig. 4. Alternately, measurement can be made by using a digital inclinometer mounted on a 12 - in. (300 mm) beam or similar instrument with accuracy as stated in 1.1.1. Measuring 12 - in. (300 mm) lengths can account for local variations in slope that may be difficult for a person in a wheelchair or using other mobility aids to use.

Measuring one - foot (300 mm) lengths allows for a reasonable check on local variation that can be accomplished easily and inexpensively with a 2 - ft digital inclinometer or other available instruments.

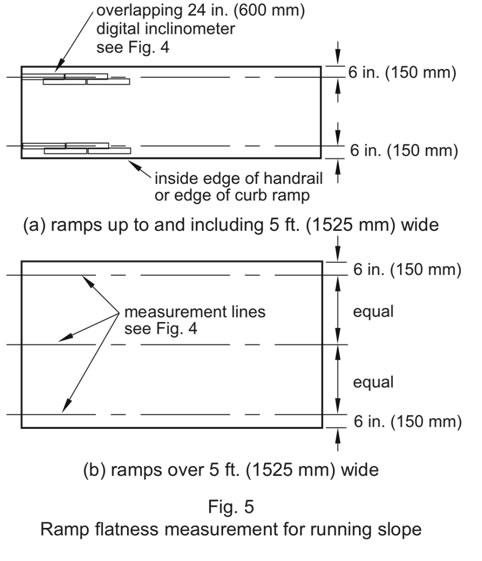

For ramps from 36 in. (915 mm) up to, and including, 5 ft (1525 mm) wide between handrails measure along two lines parallel to the length of the ramp. Each line should be approximately 6 in. (150 mm) from the inside (ramp side) edge of the handrail. For ramps where handrails are not used, such as curb ramps, measure 6 in. (150 mm) from the edge of the ramp. See Fig. 5(a).

For ramps over 5 ft (1525 mm) in width between handrails measure along an additional line for each additional 36 in. (915 mm) of width or fraction thereof beyond 5 ft (1525 mm). The additional line or lines should be spaced equidistant between the two outside measurement lines. See Fig. 5(b).

Measurement at 6 inches from the handrail or edge of curb ramps is approximately where the inside wheel of a wheelchair would be if the handrail is being used.Requiring measurement along the running slope for every additional 36 inches means that measurements will always be taken to account for a distance between 24 inches and 42 inches. This is approximately where the path of a wheelchair or other mobility aids would be used without requiring excessive lines of measurement for wide ramps.

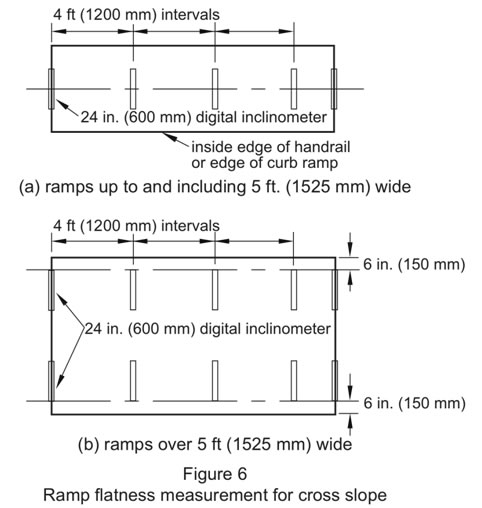

1.1.14 Flatness of ramp cross slope. For ramps, measure flatness of cross slope by placing a 24 - in. (600 mm) digital inclinometer perpendicular to the line of travel at 4 ft (1200 mm) intervals with not less than two measurements per ramp. For short ramps where only two measurements are made, measure cross slope at the top and bottom of the ramp. For ramps up to and including 5 ft (1525 mm) wide between the handrails, measure cross slope in the center of the ramp. See Fig. 6(a).

Because most exterior ramps will be 5 ft wide or less and the most common path of travel would be approximately in the middle of the path it seems reasonable to measure at the center of the ramp.

For ramps over 5 ft (1525 mm) wide between handrails, measure along both handrails with one end of the digital inclinometer placed at the line used to measure running slope. See Fig. 6(b). In addition to the measurement locations in 1.1.14, if a portion of the ramp appears to be steeper than 1:48 (approximately 2%) measure at that location as well.

As the ramp gets wider, users may tend to travel toward one side or the other, especially if the ramp is not a curb ramp and has handrails.

1.1.15 Flatness of ramp landings. Measure ramp landings at the midpoints of each landing in each direction using a 24 - in (600 mm) digital inclinometer. Edges of the ramp landing should coincide with the cross slope measurements as described in Section 1.1.12.1.1.16 Alternate measurement tools. Ramps may be measured with instruments other than a digital inclinometer if they provide the data required for evaluation of tolerances as given in Sections 1.2.5, 1.2.6, and 1.2.7. If the F - number system is used ramps should have a minimum FF of 25. Measure running slope along the same lines of measurements as stated in Section 1.1.13

Although the F - number system can be used to measure surface flatness for smooth surfaces it requires expensive equipment and workers trained to do the measurement.

An FF of 25 provides for a flatness of approximately ¼ in. in 10 ft (6 mm in 3050 mm). Waviness index may be a more appropriate measure to include if floor profilers are used. The waviness index method is described in ASTM E 1486, Standard Test Method for Determining Floor Tolerances Using Waviness, Wheel Path and Levelness Criteria.

1.1.17 Stairs. Measure cast - in - place stairs for both riser height and tread depth of each riser and tread. For stairs 60 in. (1520 mm) or less in width, measure along a line approximately 18 in. (460 mm) from the wall or outside edge of the stair. For stairs with intermediate handrails take additional measurements approximately 15 in. (380 mm) on both sides of the intermediate handrail.

Measuring about 18 inches from the wall or edge of the stair places the measurement about where foot traffic is most likely.

Measure stair riser height as the vertical dimension between tread nosings. If a tread slopes for drainage, use a level or digital inclinometer to extend the line of the upper nosing to allow measurement to the nosing below.

This is consistent with the Life Safety Code method of measurement and reflects the position on a tread that a person’s foot is most likely to contact, especially going down a stair. However, requiring the use of a level makes measurement more difficult and/or time consuming. If treads sloped uniformly for drainage, measurement could be made at the riser, from nosing to tread below because the measurement would be the same as using a level to measure from the back of the tread.

For exterior stairs sloped from the riser to the nosing for drainage, measure the slope of each tread using a digital inclinometer placed along a line as indicated in 1.1.17.

1.2 Suggested tolerances

1.2.1 Walks and other non - ramp surfaces. When overall running slope for walks is measured according to Section 1.1.3 a recommended tolerance for running slope is +1%. When overall cross slope for sidewalks is measured according to 1.1.4 a recommended tolerance for cross slope is +0.5%.

1.2.2 When flatness of running slope for an accessible surface other than a ramp is measured according to Section 1.1.5 no more than 20% (rounded to the nearest whole number) of the measurements should exceed ±1/4 in. in 10 ft (±6 mm in 3 m). When flatness of cross slope for an accessible surface other than a ramp is measured according to Section 1.1.6 at least 80% (rounded to the nearest whole number) of the measurements should not exceed a 2% slope. The remaining measurements should not exceed a 2.5% slope.

1.2.3 Landings. Both measurements of ramp landings as described in Section 1.1.15 should not exceed a plus tolerance of 0.5%.

1.2.4 When local horizontal discontinuities and vertical alignments are measured according to Section 1.1.9 a recommended tolerance is ±1/8 in. (3 mm).

1.2.5 Ramps. When overall running slope and cross slope for accessible ramps are measured according to Sections 1.1.11 a recommended tolerance for these slopes is +0.5%.

In the ideal case, planning for a 7.5% running slope allows for construction inaccuracies while still maintaining the required 1:12 slope. However, when a design slope of 1:12 is indicated a tolerance of +0.5% is reasonable.

Many accessibility experts consider a 2% cross slope to be the maximum. However, there is conflicting research concerning the need to have a 2% maximum cross slope and that the actual maximum depends on user type (wheelchair, walker, cane, etc.), length of travel, and other variables. It seems reasonable to allow a +0.5% tolerance for ramp slopes and cross slopes.

1.2.6 When local variations (flatness) in running slope of ramps are measured according to 1.1.13 at least 80% (rounded to the nearest whole number) of the measurements should not exceed an 8.3% slope. The remaining measurements should not exceed a 10% slope.

Allowing a small percentage of localized slopes to exceed 8.3% is based on the allowable slopes in ADA/ABA - AG (2004) for existing buildings of 1:8 (12.5%) for maximum rises of 3 inches and 1:10 (10%) for maximum rises of 6 inches. The 1980 ANSI A117 standard also allowed this with the additional provision that an existing ramp slope of up to 1:8 could have a maximum run of 2 feet (0.6 m). Allowing 20% of local variations to slope up to 10% seems reasonable for a distance of one foot. This would mean that localized dips and high points in a 2 - foot distance would be about ¼ in. (6 mm) or a little less.

1.2.7 When local variations (flatness) for cross slope of ramps are measured according to 1.1.14 at least 80% (rounded to the nearest whole number) should not exceed a 2% slope. The remaining measurements should not exceed a 2.5% cross slope. When four or fewer measurements are made, only one should not exceed a 2.5% cross slope, while the others should not exceed a 2% slope

1.2.8 Exterior stairs, cast - in - place. When cast - in - place exterior stairs are measured according to Section 1.1.17 the requirements of the local building code shall govern tolerances.

PART III: Appendices

Industry tolerances developed as part of this project

The following is an excerpt from the 2009 TCA Handbook, published by the Tile Council of North America.

Accessibility:

When ceramic tile is used as the flooring surface, design professionals should consider the following, based on ANSI A108.01 and A108.02, where accessibility is a primary consideration.Accessible - Changes in Level:

Changes in level up to 1/4” may be vertical and without edge treatment. Changes in level between 1/4” and 1/2” shall be beveled with a slope no greater than 1:2. Changes in level greater than 1/2” shall be accomplished by means of a ramp. The maximum slope of a ramp in new construction shall be no greater than 1;12. Ramps where space limitations prohibit this may have slopes and rises as follows: a slope between 1:10 and 1:12 is allowed for a maximum rise of 6”, and a slope between 1:8 and 1:10 is allowed for a maximum rise of 3 inches. A slope greater than 1:8 is not allowed.Accessibility - Flatness and Lippage:

With regard to flatness, the amount of substrate variation generally is reflected in the finished tile installation. For any application, a tiled floor should comply with the flatness requirements in ANSI A108.02: “no variations exceeding 1/4” in 10 feet from the required plane.” Conformance to this standard requires that subfloor surfaces conform to the following: no variation greater than 1/4” in 10 feet, nor 1/16” in 1 ft. from the required plane. For modular substrate units, such as plywood panels, adjacent edges cannot exceed 1/32” difference in height. Additionally, the effect from irregularities in the substrate increases as the tile size increases. A subsurface tolerance of 1/8” in 10’ may be required.Because the flatness of wood and concrete substrates can change over time, it is recommended that the designer make provisions for evaluating substrate flatness just before installation of the tile. Project specifications should make clear which trade is responsible for the required alterations if the subfloor is found not to be in compliance with the flatness requirements. Alternatively, the designer may choose to incorporate a mortar bed method or a pourable underlayment installed by the tile contractor to ensure substrate flatness sufficient to facilitate a flat tile installation.

Lippage is most significantly influenced by substrate flatness and tile warpage. Allowable lippage is calculated by adding the actual warpage of the tile supplied, plus either 1/32” (if grout joints and 1/4” or wide). Specifying wider grout joints allows for more gradual changes. To minimize lippage due to arpage, specify tile that meets the dimensional requirements for rectified tile according to ANSI A137.1, and use a larger grout joint. Some patterns, such as a 50% off - set (brick - joint) pattern, accentuate the effects of warpage and result in more lippage than other patterns would. Cushioned or beveled - edge tiles can minimize the effects of lippage.

In addition to taking measures to ensure a flat substrate, designers should consult with the tile manufacturer to discuss grout joint size and tile and pattern selections that will minimize issues relating to flatness and lippage.

The following are the tolerances published by the Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute as a result of this project.

Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute: Construction Tolerances for Segmental Concrete Pavements

This guideline applies to construction of interlocking concrete pavements (concrete pavers), permeable interlocking concrete pavements (Plep), and precast concrete paving slabs.

|

Setting Bed Materials |

Joint Widths |

Construction Tolerances |

|---|---|---|

|

Sand setting beds for concrete pavers and paving slabs |

Joint width between adjacent units |

1/16 in. (2 mm) to 3/16 in. (5 mm) |

|

Bituminous setting beds for concrete pavers and paving slabs |

Joint width between adjacent units |

1/16 in. (2 mm) to 3/16 in. (5 mm) |

|

Mortar setting beds for concrete pavers and paving slabs |

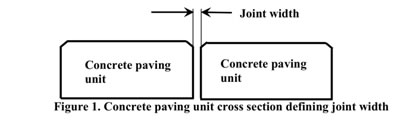

Joint width between paving units with no chamfers (See Figure 1) |

Maximum 3/8 in. (10 rom) - Joints betweenindividual paver units shall be mortared flush with adjacent pavers. |

|

Mortar setting bedsfor concrete pavers and paving slabs |

Joint width between paving units with chamfers (See Figure I) |

Maximum 3/8 in. (10 rom) - The surface of the mortared joint meets the bottom of the chamfers between adjacent pavers. |

|

Open - graded aggregates for PICP |

Joint width between paving units (See Figure 1) |

oto +3/16 in. (5 mm) of the paver manufacturer's recoromendedjoint width dimension |

|

Pedestals for supporting precast concrete paving slabs (ie., 12 x 12 in.(300 x 300 mm) and larger length x width) |

Joint width between paving slabs resting on pedestals (See Figure I) |

oto+1/8 in. (3 rom) of paving slab manufacturer's recommended joint width dimension for pedestal setting materials |

|

|

||

|

Attribute |

Segmental Concrete Paving Products & Cbaracteristics |

Construction Placement & Surface Tolerances |

|

Joint or bond lines |

All segmental concrete paving products: Horizontal deviation |

Maximum ±1/2 in. (15 mm) horizontal deviation from either side of a 50 ft (15 m) string line ]lUlled over a ioint or bond line |

|

Laying Pattern |

Laying pattern concrete pavers and PICP: Laying pattern .. |

|

|

Slope in direction of travel |

All segmental concrete paving |

+0.5 percent, no requirement for minus |

|

Slope perpendicular to direction of travel |

All segmental concrete paving |

+0.5 percent, no requirement for minus |

|

Surface smoothness |

All segmental concrete paving products: Variation in height between adiacent units (lippage) |

Maximum 1/8 in. (3 mm) |

|

Surface flatness |

All segmental concrete paving products: Surface tolerance |

±3/8 in. (10 mm) over 10 ft (3 m), noncumulative |

Compilation of Instruments and Measurement Methods for Surface Accessibility

During the course of this project the following information was developed as background information to assist industry in developing their guidelines and standards.

Measuring instruments and accuracy

There are many instruments that are currently available for measuring distances and angles as well as the surface roughness of accessible elements. These range from inexpensive, moderately accurate measuring tapes and carpenter’s levels to extremely accurate, automated electronic devices costing tens of thousands of dollars. The problem is not a need for a good measuring instrument but an agreement on which instruments to use and a protocol for using them to check for accessibility compliance.

Generally, a measurement device should read one unit more accurate than the required tolerance reading (one more decimal place or fractional graduation).

The Precast Concrete Institute recommends that the precision of the measuring technique used to verify a dimension should be capable of reliably measuring to a precision of one - third the magnitude of the specified tolerance.

Metal measuring tapes are the most commonly used tools for measuring distances. They are inexpensive, easy to use, and are available in English or metric units. Most tapes used in construction are graduated in units of 1/16 inch or millimeters. Accuracy depends on the quality of manufacturing, how they are maintained, and correctness of use.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology publishes tolerances for metal tapes in its Handbook 44, Section 5.52.

|

Maintenance and Acceptance Tolerances, in Excess and in Deficiency, for Metal Tapes |

|

|---|---|

|

Nominal interval from zero, ft |

Tolerance, in |

|

6 or less |

1/32 |

|

7 to 30, inclusive |

1/16 |

|

31 to 55, inclusive |

1/8 |

|

56 to 80, inclusive |

3/16 |

|

81 to 100, inclusive |

1/4 |

From NIST Handbook 44, Section 5.52, p. 5 - 12.

http://ts.nist.gov/WeightsAndMeasures/h44 - 07.cfm.

The NIST Handbook 44, Section 10.3 gives the following rules for the reading of indications on graduated scales if it is desired to read or record values only to the nearest graduation. If the indicator is between two graduations, but is closer to one graduation than it is to the other, the value of the closer graduation is the one to be read or recorded. “In the case where, as nearly as can be determined, the indicator is midway between two graduations, the odd - and - even rule is invoked, and the value to be read or recorded is that of the graduation whose value is even.” In most cases readings can be no more accurate than the smallest graduation.

Carpenter’s levels are used for setting level and plumb only. To determine angles the level must be used with a measuring tape to determine slope. This introduces several sources of possible errors, but uses inexpensive and readily available tools.

Digital inclinometers (SmartTool®), while slightly more expensive than standard levels, are easy to calibrate and use and can measure slopes in degrees, percent, and fractions per foot. They have an accuracy of 0.1 degree and come in 2 - foot and 4 - foot lengths. The individual electronic module can also be mounted on other devices to create customized measuring instruments.

Transits and construction lasers are useful for setting or measuring overall elevation points to determine a total slope. Most construction lasers have an accuracy of ±1/16 inch in 100 feet (1.6 mm in 30.5 m) and even greater accuracies in shorter distances. While these instruments have the necessary accuracy to determine distances and elevation points, they are not as well suited for measuring local variations of slope over small distances.

Electronic instruments have been developed to measure floor flatness. Originally created to measure the flatness of concrete floors in critical applications such as narrow - aisle warehouses, these devices can be used to measure slope flatness. Their disadvantages include a high initial cost and training needed for their proper use or the employment of a testing agency. These devices were developed to more accurately and easily measure floors according to the F - number system and the waviness index, which are described later in this paper. Electronic instruments include the F - meter, Dipstick®, and FloorPro®. Other devices are listed in the appendix.

Laser scanners use laser beams to automatically develop a three - dimensional image of a space. These types of instruments could be used to measure floor flatness and level but they are very expensive, require training, and give accuracies in excess of what is needed for accessible design.

The SmartWheel is a wheelchair - mounted device for measuring propulsion parameters that can be used to compute forces, acceleration, rate of rise, velocity, stroke length, and other aspects of wheelchair use. The SmartWheel has been accepted as a measurement tool for the ASTM PS 83 - 97/F1951 Standard on Playground Surface Accessibility.

In addition to the instruments discussed above, during the course of this project the city of Bellevue, Washington developed a Segway - mounted device to survey the city’s sidewalks and curbs to determine if they met accessibility standards. It used an ultra - light inertial profiler (ULIP) manufactured by Starodub, Inc. in Kengington, MD. This instrument gives a very small sampling interval of about 0.5 mm at maximum speed. Although providing very accurate data and the ability to extrapolate to longer intervals, there still needs to be a standard for slope, flatness, and smoothness at longer intervals.

Some existing measurement protocols

Currently there are no generally accepted measurement protocols for determining the slope, flatness, or waviness of floor surfaces in terms of accessibility. Some people use spot elevations, some use a 10 - foot straightedge, some use a 2 - foot digital inclinometer, while others may use special devices that measure slopes in 1 - foot increments. ASTM E1155 and ASTM E1486 do prescribe the methods for determining floor flatness and waviness using the F - number system and waviness index, but these standards are not mandated for testing for accessibility, nor are there any standards for accessibility that can be tested other than overall slope of ramps or local slope. There is also no accepted standard method for using a digital inclinometer, lasers, or other surveying equipment to measure ramp slope and cross slope.

Some of the currently available methods of measuring flatness and slope are outlined below. Some of these methods are standardized and others are suggested methods.

10 - foot straightedge method

This is the classic method for determining the flatness of concrete and other types of finished floors. When used as a specification or requirement, a maximum deviation in length under the straightedge is given, such as “no point shall exceed 1/4 inch under a 10 - foot straightedge.” However, there is no standardized protocol to measure deviations in lengths less than ten feet. The same problem exists when measuring slope. There is no way to measure a localized slope that may actually be greater than the overall slope of the straightedge.

The 10 - foot straightedge method has been a standard in ACI - 117, Standard Tolerances for Concrete Construction, for many years and is optional as part of ACI 117. When the 10 - foot straightedge method is used for random traffic floors, ACI 117 sets the minimum number of samples required at 0.01 times the floor area, measured in square feet. For ramps ACI 117 refers to RMS Levelness tolerance as defined in paragraph 4.11 in ASTM E - 1486.

Department of Justice method

In the tips and techniques section of “Survey Tools and Techniques,” (www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/ckstools.htm) the checklist states that slopes can be measured in three ways: with a land survey to shoot grades, using a digital level, or using a 24 - inch long builders level and tape measure.

The directions for using a level are as follows. “Using a builders level, place the level on the pavement at the steepest point parallel to the direction of the slope. While holding the uphill end of the level on the pavement, place a pencil under the other end and roll it toward the uphill end of the level until the horizontal air bubble shows level. Use the tape measure and measure the open gap at the downhill end of the level to establish the critical dimension. For a 1:50 slope this is 1/2 inch; for a 1:20 slope it is approximately 1 - 1/4 inch and for a 1:12 slope it is 2 inches.”

F - number system

The F - number system, ASTM E 1155, Standard Test Method for Determining FF Floor Flatness and FL Floor Levelness Numbers, was developed primarily to aid in the construction of superflat industrial floors. When tolerances are specified using the F - number system both the overall levelness and the flatness can be defined. The flatness number also gives an indication of the “bumpiness” of the surface.

The F - number system develops two number ratings, the FF and the FL. The FF defines the maximum floor curvature allowed over a 24 - inch (600 mm) length computed on the basis of successive 12 - inch (300 mm) elevation differentials. The FL defines the relative conformity of the floor surface to a horizontal plane as measured over a 10 - foot (3.05 m) distance. Statistical sampling procedures are used to determine a floor’s F - numbers. F - numbers are reported as two numbers such as FF30/FL24. The higher the number, the flatter and more level the floor.

There are several methods given in ASTM E 1155 that can be used to measure a floor and develop the F - numbers. However, in practical terms, sophisticated electronic measuring devices developed specifically for this purpose are used. They are expensive and require some amount of training or a testing agency can be employed.

Although direct equivalents are not appropriate, an FF of 25 approximately correlates to a ¼ inch variation under an unleveled 10 - ft straightedge. An FF of 50 approximately correlates to a 1/8 - inch variation under a 10 - ft straightedge. Other approximate correlations are shown in the following table.

F - number

Gap under an unleveled 10 - ft straightedge, in (mm)

FF 12

1/2 in (13)

FF 20

5/16 in (8)

FF 25

1/4 in (6)

FF 32

3/16 in (4.8)

FF 50

1/8 in (3)

Concerning issues of vibration and rollability, the F - number system is probably a better measure than the straightedge because it takes into account local variations of flatness. Although it was developed to measure level floors, it can be used measure sloped floors.

For slabs - on - grade the F - numbering system works well. However, to determine the F - number for levelness of suspended slabs, measurements must be taken within 72 hours of floor installation and before shoring and forms are removed. For elevated slabs under current standards, the specified levelness and flatness of a floor may be compromised when the floor deflects when the shoring is removed and loads applied. However, local variations that could affect vibration and rollability would probably not be affected to any significant degree by slab deflection.

Additional limitations with the F - number system are that the measurements do not cross construction joints and only come within two feet from penetrations. Construction joints as well as other types of joints can affect vibration and rollability. The F - number system is optional as part of ACI 117 - 06.

Waviness Index

The Waviness Index, ASTM E 1486, Standard Test Method for Determining Floor Tolerances Using Waviness, Wheel Path and Levelness Criteria, was developed in response to the discovery that the F number system was not particularly responsive to floor deviation wavelengths between 4 and 15 feet. FF detects floor quality for wavelengths of 1.5 to 4 feet. FL detects variations when wavelengths are from 15 feet to 80 feet. The Waviness Index provides information about flatness in the wavelength range between 1.5 feet and 20 feet, which was deemed important to measure floor flatness as required by forklift trucks.

The Waviness Index measures the bumps and dips in a floor surface as the average of deviations up or down from the mid - points of 2 - , 4 - , 6 - , 8 - , and 10 - foot chords. In addition to providing a single Waviness Index number, the measurement method can also provide a computer - simulated deviation from a 10 - foot straightedge. This gives similar values as using a straightedge manually, but with the advantages of following a defined profile line according to the procedures in ASTM E 1486 and using an instrument that more accurately measures deviations.

As with the F - number system, determining the Waviness Index can be performed in a variety of ways, but practically, a sophisticated instrument must be used along with computer software that performs the calculations and reporting. The test method does NOT apply to clay or concrete unit pavers. The Waviness Index method is also optional as part of ACI 117 - 06.

Original research for ANSI A117.1 (1957 - 1961)

In the original research for ANSI A117.1 - 1961, American National Standard Specifications for Making Buildings and Facilities Accessible to, and Usable by, the Physically Handicapped, ramps were assessed for flatness based on measuring 18 - inch increments on both edges of the ramped surface. Both slope and cross slope were measured. These guidelines for measurement were deleted from later versions of the standard.

Unified Facilities Guide Specifications

In Section 02752, Portland Cement Concrete Pavement for Roads and Site Facilities, published by the National Institute of Building Sciences, it is stated that surfaces should be tested with a 4 - meter (12 ft) straightedge in both a longitudinal and transverse direction on parallel lines approximately 4.5 meters (15 ft) apart. The straightedge is to be held in contact with the surface and moved ahead one - half of the length of the straightedge for each successive measurement. The amount of surface irregularity is to be determined by placing the straightedge on the pavement surface and allowing it to rest on the two highest spots covered by its length and measuring the maximum gap between the straightedge and the pavement, in the area between the two high points.

Suggestion by Eldon Tipping

As published in Concrete Construction magazine, September 1998, Eldon Tipping made suggestions for a specification for sloped random - traffic floors such as parking decks, ramps, and other sloped surfaces, but not necessarily for accessible ramps.

Mr. Tipping suggested that each ramp should be evaluated independently as a Random - Traffic Test Surface. Slopes were to be measured with a Dipstick Floor Profiler (Face Construction Technologies) within 16 hours after completion of final finishing, and where applicable, before removal of any supporting shores. Sample measurement lines were to be parallel or perpendicular to slopes shown on the drawings. Measurement lines that were parallel to slopes were to connect elevation control points. At least two sample measurement lines were to be taken per bay and in perpendicular directions where slopes permitted. The minimum length of measurement lines perpendicular to the slope were to be one column bay. In the testing report, slope departures were to be calculated at 5 - foot overlapping intervals along each sample measurement line. His suggestions for tolerances are given later in this paper.

Suggestions by Jean Tessmer

As published in Concrete Technology Today, April 2001, Jean Tessmer, accessibility consultant for Space Options, suggested that ramp slopes be measured with a digital inclinometer mounted to measure 1 - foot increments. The line of measurement should be parallel to the long edge of the ramp. Longitudinal measurement lines should be spaced 3 feet apart, but in no case should fewer than two lines be used. For cross slopes, measurements should be taken every 6 feet.

Construction Specification Institute

While developing suggested tolerances for surface materials, the Construction Specifications Institute developed a suggested method for measuring ramp slopes. These have neither been adopted nor are they published.

CSI suggested taking measurements using a digital inclinometer with an accuracy of ±0.1 degree mounted on an aluminum beam with rotating ball joint on metal pads at 12 inches on center. For longitudinal lines, measurements were to be taken in minimum 5 - foot lengths running parallel to the long dimension, with one measurement line per 3 feet of width and within 2 feet of edges, spaced equidistant apart, with not less than two lines evaluated for each ramp.

For transverse lines, measurements were to be taken in minimum 2 - foot lengths along a line running parallel to the long dimension, with one measurement line per 6 feet of length and within 2 feet of ends, spaced equidistant apart, with not less than two lines evaluated for each ramp.

Standards

Industry Standards

- ACI 117 - 2006 Standard Specifications for Tolerances for Concrete Construction and Materials

- ASTM E 380 Standard Practice for the Use of the International System of Units (SI); The Modernized Metric System.

- ASTM E 621 - 94 (1999)e1 Standard Practice for the Use of Metric (SI) Units in Building Design and Construction

- ASTM E 1155 - 96 (2001) Standard Test Method for Determining FF Floor Flatness and FL Floor Levelness Numbers

- ASTM E 1486 - 98 (2004) Standard Test Method for Determining Floor Tolerances Using Waviness, Wheel Path and Levelness Criteria

- ASTM E 1486M - 98 (2004) Standard Test Method for Determining Floor Tolerances Using Waviness, Wheel Path and Levelness Criteria (Metric)

- ASTM F 802 - 83(2003) Standard Guide for Selection of Certain Walkway Surfaces when Considering Footwear Traction

- ASTM F 1637 - 02 Standard Practice for Safe Walking Surfaces

- ASTM F 1951 - 99 Wheelchair Work Measurement Method

- ASTM PS 83 - 97/F 1951 Standard on Playground Surface Accessibility

- ASTM WK 3539 (Work item) Practice for Reporting Uncertainty of Test Results and Use of the Term Measurement Uncertainty in ASTM Test Methods

- CSA A23.1 - 04/A23.2 - 04 Concrete Materials and Methods of Concrete Construction/Methods of Test and Standard Practices for Concrete. Canadian Standards Association, Toronto, 2004.

- CSA A23.1 - 94, Treatment of Slab or Floor Surfaces: Surface Tolerances, Straightedge Method. Canadian Standards Association, Toronto, 1994.

- ISO 1000:1992 SI units and recommendations for the use of their multiples and of certain other units

- ISO 1000/Amd1:1998 Amendment to ISO 1000

- ISO 1803:1997 Building construction - Tolerances - Expression of dimensional accuracy - Principles and terminology

- ISO 2631 - 1:1997 Mechanical vibration and shock - Evaluation of human exposure to whole - body vibration - Part 1: General requirements

- ISO 2631 - 2:2003 Mechanical vibration and shock - Evaluation of human exposure to whole - body vibration - Part 2: Vibration in buildings (1 Hz to 80Hz)

- ISO 2631 - 5:2004 Mechanical vibration and shock - Evaluation of human exposure to whole - body vibration - Part 5: Method for evaluation of vibration containing multiple shocks

- ISO 3443 - 1 Building construction - Tolerances for building - Part 1: Basic principles for evaluation and specification

- ISO 3443 - 2 Building construction - Tolerances for building - Part 2: Statistical basis for predicting fit between components having a normal distribution of sizes

- ISO 3443 - 3 Building construction - Tolerances for building - Part 3: Procedures for selecting target size and predicting fit

- ISO 3443 - 4 Building construction - Tolerances for building - Part 4: Methods for predicting deviation of assemblies and the distribution of tolerances

- ISO 3443 - 5:1982 Building construction - Tolerances for building - Part 5: Series of values to be used for specification of tolerances

- ISO 3443 - 6:1986 Tolerances for building - Part 6: General principles for approval criteria, control of conformity with dimensional tolerance specifications and statistical control - Method 1

- ISO 3443 - 8:1989 Tolerances for building - Part 8: Dimensional inspection and control of construction work

- ISO 4463 Measurement methods for buildings - setting out and measurement - permissible measuring deviations

- ISO 4464 Tolerances for buildings - Relationship between the different types of deviations and tolerances used for specifications